Labour market remains strong but consumer confidence is taking a hit

Falling real wages reducing consumer confidence

A core component of economic activity is household expenditure, which accounts for around 60% of the economy in the UK.

A period of rising inflation in the UK (largely a result of the devaluation of sterling and increased energy prices) is starting to negatively affect real wages, which in turn is reducing consumer confidence and household expenditure. Latest data from the Office for National Statistics show that in the period March-May, average weekly earnings for employees in nominal terms (that is, not adjusted for price inflation) grew by 1.8% on the previous year. However, inflation over the same period ran at 2.9% compared to the previous year, meaning that in real terms, average wages are falling.

Moreover, this is now the third quarter in a row where real wages have declined, the first time this has occurred since 1976. This is clearly now having a knock-on impact into business activity, with service sector industries feeling less and less confident about current and future levels of growth.

The UK service sector PMI (Purchasers Managers Index – a key barometer of business activity) has fallen for the fourth month in a row to a score of 53.4, and confidence by the sector is at its second lowest level since 2011, reflecting this reduction in household expenditure. A similar picture is being played out locally, with the most recent Coventry & Warwickshire Chamber of Commerce/Warwickshire County Council Quarterly Economic Survey also showing a fall in the service sector economic index, dropping from 66.2 to 63.7.

On both these indicators, a score above 50 indicates that the sector is still growing (and therefore shows that the service sector locally is performing at a much stronger rate than the national average), but the decline is a concern given the size and importance of the sector to the overall UK economy.

The manufacturing sector, on the other hand, is still benefiting from the devaluation in sterling, which makes our exports relatively cheaper. Overseas orders are holding up strongly and generally outweighing the slight decline in domestic sales.

The labour market still very strong, but productivity is a key concern

The fall in real wages is somewhat strange when put against the backdrop of extremely high employment rates and correspondingly low levels of unemployment.

General economic theory suggests that when unemployment is low, businesses need to increase wages to attract people to work for them, leading to wage inflation. In the UK, the employment rate (the proportion of people of working age in employment) now stands at 74.9% (the highest levels since comparable records began in 1971) and the unemployment rate is at 4.5% (the lowest since 1975). In Warwickshire, the figures are even stronger, with an employment rate of 77% and unemployment at just 2.9%.

As a result, competition for labour is strong and many businesses continue to report skills shortages and recruitment difficulties, highlighted in many recent national and local surveys. The reason why this is not leading to wage increases is unclear and rather puzzling.

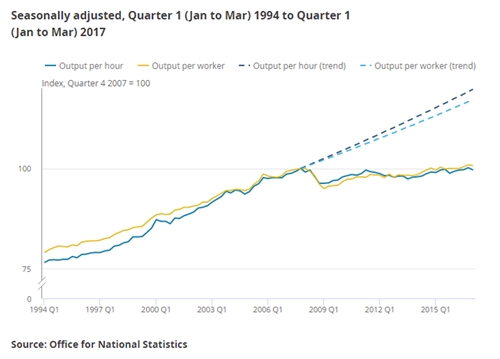

Some explanations focus around the growth of low-wage jobs, temporary/flexible contracts and the utilisation of relatively cheap overseas labour; others around the potential uptake (or perhaps more likely at the moment, the threat of uptake) of automated technologies and artificial intelligence which increasingly have the potential to replace workers. Both have merit and are no doubt contributing but another factor is also likely to be the worryingly low levels of productivity within the UK economy, which are limiting the competitiveness of companies and their ability to raise wages. Latest productivity figures show that labour productivity (as measured by output per hour worked) has fallen by 0.5% in the first quarter of 2017.

Levels of productivity within the economy are back to the levels they were in 2007, effectively meaning that we have now had a decade of no productivity improvements. This is particularly striking when compared to what levels of productivity (and therefore economic output and living standards) should be had they followed the same growth trajectory that we were experiencing before the last recession – shown in the graph below.

The importance of effective skills on this whole agenda cannot be overstated. Higher skilled workers can help drive productivity levels upwards, enabling businesses to increase wages, which can then help encourage consumer confidence and household expenditure, ultimately leading to stronger economic growth. This is why the county council is particularly focusing on the key area of helping to equip the county's workers with the skills they need.